Giant of Economics: John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946)

John Maynard Keynes was without question the most influential economist of the twentieth century. Not only he turned the abstract world of academic economics topsy-turvy – since then theoretical economics was changed completely – but also affected the bread and butter world of every day lives when economics advisors steeped in Keynesianism offer remedies for economy ailments that affect every one of us.

John Maynard Keynes was without question the most influential economist of the twentieth century. Not only he turned the abstract world of academic economics topsy-turvy – since then theoretical economics was changed completely – but also affected the bread and butter world of every day lives when economics advisors steeped in Keynesianism offer remedies for economy ailments that affect every one of us.

Who was this remarkable Keynes? This brief essay examines his life and how he came to develop his ideas.

Born the same year and in the same country which Karl Marx died, despite having their lives back to back each other, Keynes and Marx could not have been more different. While Marx sought to precipitate the collapse of capitalism and in its place would emerge communism, Keynes wanted to save capitalism from the growing threat of collectivism. It was not only their aim that they differed; their personalities were at opposite poles. Marx was morose, almost a recluse, a painfully slow and difficult writer, dedicated his entire life to his magnum opus (only to finish volume 1 of Das Kapital) and lived in a constant dire financial circumstance. Keynes, on the other hand, was a man of worldly affairs who loved the limelight, straddled between the academic and political world, a consummate and witty writer, in addition to economics, made major contributions in the field of mathematics and biography writing and died a very rich man. Unlike towards most economists, when you are justified to mock them with the sarcasm “if you are so smart; why ain’t you rich”, you cannot do likewise with Keynes for his flair for investing was second to David Ricardo; no third place among economists, for your information.

When we mortals think Keynes would have his hands full already, the brilliant economist still found time for collecting books, founding an Arts theatre, editor of an economics journal and acting as trustee or bursar for several organisations. He seemed to live a 25-hour day and an eight-day week. Whatever and however he did it, he lived intensely in the present, not wasting a tick of his life.

Keynes was a member of an elite club called the Apostles, whose London extension became known as the Bloomsbury Group which boasted member intelligentsia like Bertrand Russell, G.E. Moore, Lytton Strachey, and Virginia Woolf. These members often met behind bolted door every week to discuss basically three things: what they knew, what they thought and what they were. With such elevated view about themselves, they came to see themselves as “real” and others as “unreal”, or in Kantian’s terminology “Phenomenal”. (See Immanuel Kant). Keynes, notwithstanding, once remarked that “I get the feeling that most of the rest never see anything at all — too stupid or too wicked”. However, besides bloating Keynes’ ego, the club also moulded much of his belief with which he carried throughout his life: 1. Philosophy King, 2. Intuition, 3. Ethics, and 4. Analytical Philosophy.

As a member of the Apostles, he believed he could judge with confidence what is good and right for himself and the community at large. A small group of intelligent and responsible people, fashioned after Plato’s philosophy kings, is suffice to make decisions to ensure smooth running of society, without sacrificing individual liberty like in a totalitarian society. He set the example himself by being an advisor on economic matters to the British government in both World Wars and a negotiator in post World War II period.

G.E. Moore gave Keynes the idea of intuition. In his Principia Ethica Moore argued all ethical actions are definable in the word “Good” but the word “Good” itself is non-natural property and therefore undefinable and could be known only by intuition. In the same way, Keynes argued in his Treatise on Probability that probabilities are logical relations which are known by intuition (among people the likes of Keynes). Though, another equally competent mathematician Frank Ramsey expressed his doubts: “He (Keynes) supposes…they can be perceive; but speaking for myself I feel confident that this is not true. I do not perceive them, and if I am to be persuaded that they exist it must be by argument.” (Ramsey). Keynes later intuited what he thought to be the “correct” economic concepts and principles, cumulating to his definitive work “General Theory of Employment, Income and Interest.”

In ethical issues, Keynes was also influenced by Moore. Since “Good” could only be intuitively perceived, Moore reasons that “(an ethical action) cannot possibly depend solely on …its own intrinsic value… It is, in fact, evident that, however valuable an action may be in itself, yet owing t its existence, the sum of good in the Universe may conceivably be made less than if some other action, less valuable in itself, had been performed.” (Moore). In other words, Keynes was a consequentialist who championed expediency over abstract right. During the two world wars, unlike his Bloomsbury friends who were staunch pacifists, Keynes contributed to the war efforts, much to the chagrin of his “real” friends. In the early 20s, Keynes argued against the return to the Gold Standard which would only temporary add prestige to British pound in the expense of retarding economic growth and increasing unemployment. He preferred solving practical problems to restoring abstract “prestige”.

Keynes’ analytical approach towards mathematics and economics was under the joint influence of Moore’s Principia Ethica and Bertrand Russell’s Principia Mathematica. In Ethica, Moore set out to “philosophise” or analyse about what other philosophers meant by the things they said about ethics — a kind of philosophy analysing the philosophy of ethics. In similar veins, Russell sought to reduce mathematics to mere logical symbols and operators and within which it would be possible to prove any mathematical theorem — a kind of mathematics to prove mathematics. Fortunately, Keynes did not do to economics what they did to ethics and mathematics or we would end up with a “Principia Economica”. Yet Keynes did question monolithic assumptions erected by classical economists, spanning from Adam Smith to David Ricardo, right up to Alfred Marshall and Arthur Pigou. And he finally tolled the death knell for classical economics with his Keynesian Revolution.

Besides being a brilliant theoretical and practising economist, Keynes had a gift of prophecy in the unfolding of socio-political and economic events. On at least two separate occasions, he proved prescient.

He believed the punitive reparations demanded by the Versailles Treaty after WWI would outstrip Germany productive capacity; thereby incurring the wrath of Germans and laying grounds for another continental war. He condemned the Allies, resigned as a senior Treasury official in the British delegation to the Versailles conference and expressed his indignation in “The Economical Consequences of Peace”, published in 1919 when Adolf Hitler was only one of the many angry Germans without jobs and futures. “If we aim deliberately at the impoverishment of Central Europe, vengeance, I dare predict, will not limp. Nothing can then delay for long that final civil war between the forces of reaction and the despairing convulsions of revolution, before which the horrors of the late German war will fade into nothing, and which will destroy… the civilization and progress of our generation.” (Keynes).

In the early 1920s, he lambasted the decision by Winston Churchill, chancellor of the exchequer at that time, to return Britain to the gold standard with an over-valued pound in another publication “The Economic Consequences of Mr. Churchill.” Keynes reasoned that the fixed exchange rate between gold and pound should be abandoned because “When stability of the internal price level and stability of the external exchanges are incompatible, the former is generally preferable”. He believed that exchange rate policy should be subordinated to the needs of the domestic economy. As far as Keynes was concerned, “”In the modern world of paper currency and bank credit there is no escape from a “managed” currency, whether we wish it or not; – convertibility into gold will not alter the fact that the value of gold itself depends on the policy of the Central Banks” … In truth, the gold standard is already a barbaric relic.” (Keynes, 1924, p170) Ultimately, Keynes lost, and from 1925 onwards, an over-valued pound ushered in a period of high employment, uncompetitive exports, fall in wages, cumulating to the General Strike of 1926. Only until in 1931, Britain decided to come off the Gold Standard. Even in the recent decades, Keynes’ prediction reverberated on the international stage. Fixed exchange rate has always been the “holy grail” of politicians for reasons we could only guess. Yet, in the last few decades, we saw the collapse of the Bretton Woods system (exchange rates linking gold) in the early 1970s; and spectacular attack on the British pound in 1992 by currency speculators, notably George Soros, which ultimately led the collapse of the fixed Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) for European currencies. What about Euro dollars? That could be only one reason why Britain remains adamantly outside this elite club.

The recession years in 1920s and 1930s Britain and the Great Depression of 1929 in America helped forge Keynes’ General Theory when persistent high unemployment baffled the economists at that time. Classical economic theory was unable to explain or offer any useful remedy for the long economic downturn. Classical economists, since Adam Smith and before Keynes, believed that market would ultimately correct itself. According to their model, a household would spend a portion of its income on consumer goods and save the rest in a bank. In a downturn, the household would cut back expenditure, and save more. Reduced demand will pile up unsold inventories and closed down factories. But, more money in the bank would put download pressure on interest rate. With the loans at a lower interest rate, a businessman would find investment project relatively more profitable and start building factories again, which will result in hiring of workers until full employment is reached. But what about time lag when businessmen could not invest as quickly as consumers allocate more income into banks. Classical economist argued a fall in wage would solve the problem. However in the 1920s and 1930s, wages did fall but unemployment continued to shot up. Involuntary unemployment, strictly speaking, was impossible. The ivory tower of classical economic theory had no solution except to wait. In classical economics, output or employment are determined by supply, that is changes in the production function (technological change like the Industrial Revolution) or changing work habits of workers (more diligent). Demand has no effect on output or employment. The only consolation these classical economist could offer was, in the words of Dr. Pangloss in Voltaire’s Candide, “Everything is for the best in the best of all possible world.”

Keynes did not share their optimism. “In the long run, we will all be dead.” (Keynes, 1924). Keynes realised that household savings and investment are asymmetrical; increase/decrease in one does not immediately translate to a corresponding decrease/increase in the other. The decision to invest by businessmen depends not merely on interest rate but also on consumer confidence, political and social stability, exchange rate and others. A situation could occur when additional savings are not invested but left idle in the reserves of banks. When household savings exceed investment, recession would take place. In latter half of 1990s, Japan’s domestic economy continued to be in the doldrums despite interest rate at an all time low of 0.5 per cent. Japanese businessmen simply refused to invest given the poor economic outlook.

At the same time, a specter is haunting Europe — the spectre of collectivism. Hitler’s Nazi Germany (See Hitler’s Banker), Stalin’s communist Russia and Mussolini’s Fascist Italy were achieving spectacular economic growth. Incidentally, their approach towards economy recovery was basically Keynesian, which is to spend one’s way out of recession, though they might not fully aware of Keynes’ theoretical work. Keynes was worry the success of collectivism might ultimately encroach on individual liberty and destroyed capitalism. Therefore, Keynes sought to save capitalism with his “General Theory” published in 1936. He wrote “I defended it (the enlargement of the functions of government), on the contrary, both as the only practicable means of avoiding the destruction of existing economic forms in their entirety and as the condition of the successful functioning of individual initiative.” (Keynes, 1936, p380). (Notice his preference for expediency over abstract right).

The General Theory was indeed a revolutionary work. He minced no words in stating the objective of his book. “…postulates of the classical theory are applicable to a special case only and not to the general case…” (Keynes, 1936, p3). Keynes believed he did for economics what Albert Einstein had done for physics. Einstein developed a generalisation under which Newton’s mechanics can be subsumed as a special case. Likewise, Keynes developed a generalisation under which classical economics can be subsumed as a special case. The details of his analysis are beyond the scope of this essay. Instead I will touch on his remedy.

Keynes prescribed a shot of “testosterone” into ailing economy to boost aggregate demand; thereby employment. This prescription is commonly known as “spending one’s way to recovery”. Government should, at appropriate time, using a mixture of fiscal policies like road construction or reduce taxation, to boost aggregate, even at the expense of a bigger budget deficit. Keynes could not be bothered how the money should be spent but spend anyhow. “”If the Treasury were to fill old bottles with banknotes, bury them…and leave it to private enterprise…to dig the notes up again…there need be no more unemployment…” (Keynes, 1936, p129).

Ever since his publication, Keynesianism dominated macroeconomic policy in the US to 1968 and in Britain to 1979. Even today, President George Bush uses tax cuts as fiscal stimulus for the faltering US economy. Similarly, in Singapore, our employers’ Central Provident Funds were cut amid of yet to recover Singapore economy. Keynesianism, I think, is here to stay.

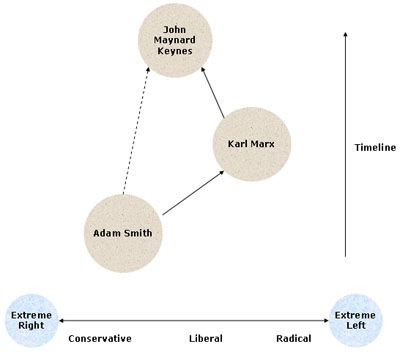

Below is a diagram I use to illustrate the three most, I think, influential economists, their time line and their stance. (Also see Adam Smith and Karl Marx)

Leo Kee Chye

Saturday, August 9, 200

Posted By

leokeechye@gmail.com

Categories

Economics

Tags

Economics